The importance of design in supporting people who have experienced violence has been one of the common themes I’ve heard on my Churchill Fellowship trip. Many comments were about young people saying that having a space that was clearly designed with them in mind made them feel truly welcome – rather than just being put somewhere originally intended either for parents or for young children.

I’ve always known it was important, but after meeting Heather Mitcheltree, a researcher currently undertaking a PhD at Cambridge looking at the design of women’s refuges, the importance of good design is now even more apparent.

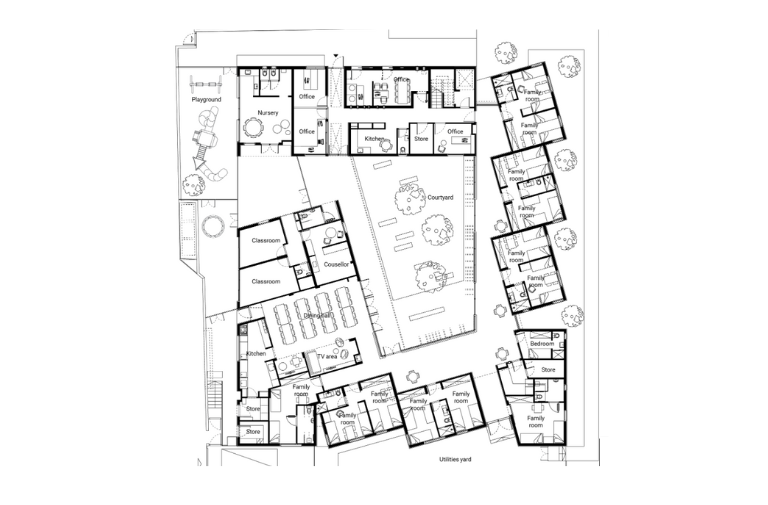

Heather’s work focuses on how the design of domestic and family violence accommodation facilities impacts on the agency, safety and perceptions of the health and wellbeing of those within the shelter environment. She is examining a range of refuges both within Australia and overseas. One of her international case studies is a refuge in Tel Aviv. The designers of this facility responded specifically to many of these issues, and it is an interesting exploration of this considered approach.

In our meeting, Heather shared some of what she’s learnt from her ongoing work, which interestingly builds on research she did (in conjunction with Blair Gardiner) with 110 homeless youth about their support needs. In particular, she’s looked at the intersection of architecture and violence and the need to both reduce visual stress (which the lay person would not necessarily recognise) and increase the therapeutic impact of the built environment.

As part of her study, Heather is doing a series of case studies, involving interviews with the women staying in refuges and the staff that are there to support them. She asks both groups about what safety means to them and what aspects of the refuge they believe contribute to the sense of safety. Another question asked of residents is what sorts of spaces make them feel safe and staff were asked what safety and security issues need to be considered.

While Heather is yet to publish her full findings, she shared a few initial observations. One that really stood out is the differences between the residents and staff in perceptions about the factors that make spaces feel safe.

For the women, it was mostly about feeling emotionally safe and the absence of fear, followed by having personal and social support, connections and being away from the person using violence. From a design perspective, this means the focus on minimising interpersonal conflicts and potential for suicidal ideation needs to be carefully balanced with keeping women safe from the perpetrators of violence.

In contrast, staff had a much stronger sense that physical safety was most important – locks, as well as rules. Staff also noted the importance of emotional safety and for a place to feel homely, which was not high on the resident’s priorities. (In some cases, the concept of ‘home’ was actually distressing, as it did not have good associations.)

In elaborating on the importance of emotional safety, once they’ve reached the shelter, the biggest burden for residents seemed to be about mental load. While physically safe, they still felt insecure and needed to regain control and create stable environments for their children.

Having personal support, connection and somewhere to relax with a few of their own things was important to feeling safe. And while design wasn’t specifically called out, ensuring that the physical restrictions didn’t contribute to the sense of not being safe was important.

Visual stress has emerged as a significant issue. Beyond the idea of bars and locks on doors, there can even be stress from elements, such as design features or lighting. Part of Heather’s aim is to be able to shift trauma-informed design from being seen as something ‘fluffy’ to using science to quantify the impacts. The work that she has been doing on visual stress is in conjunction with a fellow researcher, Cleo Valentine, and a team at Cambridge University. They have been using a tool developed by a group at Cambridge, to identify areas of higher visual stress and catalogue them, so those designing safe spaces like refuges can avoid or try to design out elements that might cause stress or be triggering.

Another interesting aspect of Heather’s research is whether refuges should remain anonymous and their locations kept secret or, as I discovered in Amsterdam, be hidden in plain sight. In Canada, you can even search online and find the locations of all refuges on a map. Heather suggested that there are design considerations for both approaches and it’s certainly a topic that is worthy of further discussion, as the paradox of hidden localities and current safety measures is interesting, in light of what her research is showing.

I hope you’ve found this interesting and encourage you to keep an eye out for Heather’s research, which will be published soon.